Leo Tolstoy, "Only Faith Can Give Truth"

Philosophy of Life

July 27 2024 06:32 EDT

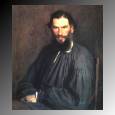

Leo Tolstoy (detail) portrait by Vasily Perov

SITE SEARCH ENGINE

since 01.01.06

Leo Tolstoy, "Only Faith Can Give Truth"

Abstract: In recognition of the fact that death is the only certainty in life, Tolstoy concludes the meaning of life cannot come from art, science, or philosophy. Only the irrational knowledge of faith can provide life's meaning.

- Explain Tolstoy's "arrest of life" from both a philosophical and a psychological point of view.

- In this reading, Tolstoy gives several different definitions of "truth." He first states "truth" as "everyday life"; he second states "truth" is "death", and finally concludes "truth" is "faith." Explain what each definition of "truth" means, and then explain what aspect of each definition has in common with the other definitions Tolstoy offers. Which, if any, of these definitions do you think most people would agree is the "truth" of their lives?

- Explain for each case, according to Tolstoy, why understanding of the fields of knowledge (science), abstract science (mathematics and metaphysics), or speculative understanding (philosophy) cannot yield substantive meaning to life? Do you agree with his assessments?

- Why does the working person, the person with the least theoretical knowledge, have no doubt about life's meaning? In what ways is Tolstoy's characterization of this type of person similar to Russell's characterization of the practical person?

- Carefully characterize Tolstoy's conception of faith. In what sense is "faith" another kind of "truth" for Tolstoy? Is the notion of "irrational knowledge" meaningful from a philosophical point of view?

- Leo Tolstoy (1828-1910) was a Russian novelist, moral

philosopher, and religious reformer.

- He made the Russian realistic novel a literary genre that ranks in importance and influence with classical Greek tragedy and Elizabethan drama. His greatest novels have been praised as "a standard by which the achievements of other novelists can be measured."

- He stressed the ethical and moral side of Christianity but

turned away from Russian Orthodoxy by rejecting the notion of

a personal relationship with God.

- The doctrine of love from the Sermon on the Mount especially impressed him.

- He condemned capitalism, private property, and the division of labor.

- He was an early champion of non-violent protest and the doctrine of passive resistance. Mohandas Gandhi having read Tolstoy's The Kingdom of God is Within You was influenced by these ideas. Gandhi briefly corresponded with Tolstoy and set up "Tolstoy's Farm," an experimental community.

- Tolstoy was very much interested in childhood education

and self-improvement.

- From the time of college on, he acquired the life-long habit of keeping a diary or journal of this thoughts, plans, and actions.

- He followed a rigorous course of self-study throughout his life.

- Some of his followers built utopias on the basis of his ideas.

- His views on living life as simply as possible led to problems with his wife after he put all his works in the public domain. He died at a railway station on his way to spend his remaining years at a monastery.

- Ideas of Interest from Tolstoy's A Confession

- Notes are arranged in response to the questions stated below in

reference to "Only

Faith Can Give Truth" selected from Tolstoy's A Confession in

Reading for Philosophical Inquiry.

- Explain Tolstoy's "arrest of life" from both

a philosophical and a psychological point of view.

- Here is a person who had everything going for him: a great author, wealth, and respect of the nation. These, he says, held at bay any question of the meaning of life.

- Note how Tolstoy describes his life in almost exactly the same terms as Bertrand Russell's practical man: "…teaching what was for me the only truth, namely, that one should live so as to have the best for oneself and one's family."

- Tolstoy experienced what he terms "An arrest of life":

he did not know how to live or what to do. The significance of

life had lost all meaning.

- The same questions: Why (do this)? Well (so what if I do)? and then (what if I don't)? In part, the questions are reminiscent of the expression, "Is that all there is?"

- From a psychological point of view, to say that Tolstoy was merely suffering a "mid-life crisis" would be to commit a psychologism.

- Tolstoy did not know how to live or what to do. Also, he expresses a sense of "beingness towards death." (Cf., the "midpoint of life curve" in the notes on Albert Camus.)

- Notice, as well, Tolstoy expresses Camus's sense of being

"undermined": "I felt that what I had been standing

on had collapsed and that I had nothing left under my feet."

- Yet, he was in full command of his mental powers.

- Again, Tolstoy predates Camus's sense of the absurd: "…my life is a stupid mean trick played on me by somebody." Tolstoy could not find any sensible meaning to a single act or to his whole life.

- "The Well of Life"—story retold from the Hindu scripture the Mahabharata: shows life's predicament graphically. (Note the drops of honey referred to in the allegory (authorship and family) are what Albert Camus will later term, "eluding" from life.)

- In this reading, Tolstoy gives several

different definitions of "truth." He first

states "truth" as "everyday life";

he second states "truth" is "death",

and finally concludes "truth" is "faith."

Explain what each definition of "truth" means,

and then explain what aspect of each definition has in

common with the other definitions Tolstoy offers.

Which, if any, of these definitions do you think most

people would agree is the "truth" of their

lives?

- First, as noted above, Tolstoy writes, "…teaching what was for me the only truth, namely, that one should live so as to have the best for oneself and one's family." Monetary and literally success helped obscure his low estimation of the value of his work.

- "The truth" is simply that fact that I

will die. Death is the truth.

- Tolstoy notes that this fact is the only certainty in life. Not only ourselves, but those we love will die.

- William Makepeace Thackeray expressed it well in chapter one of his novel Barry Lyndon, "…good or bad, rich or poor, beautiful or ugly—they are all equal now …"

- Tolstoy writes, "…faith … makes it possible to live. Faith still remained to me as irrational as it was before, but I could not but admit that it alone gives mankind a reply to the questions of life, and that consequently it makes life possible.…" Note particularly that, although Tolstoy was a Christian, he is not proselytizing for that religion. He points out that the superstitions of religion are not essential to that faith. Faith involves not reason but subjective apprehension of God or the infinite.

- By "truth," Tolstoy probably is indicating what human beings can found their life on—the basis by which, or the presupposition by which, life can have significance.

- Explain for each case, according to

Tolstoy, why understanding of the fields of knowledge

(science), abstract science (mathematics and metaphysics),

or speculative understanding (philosophy) cannot yield

substantive meaning to life? Do you agree with his

assessments?

- First, Tolstoy explains that art is an adornment of life,

a decoy of life, a diversion, a way to elude life.

- The idea is that a decoy is something which entices or lures us into a trap.

- Art and poetry are an imitation of life: a representation of reality rather than reality, itself. (Compare this idea to Plato's theory of the good).

- Consider the mundane example of the difference between the significance of seeing a movie instead of living your own life. Doesn't one stand up, walk out of the movie, and believe, "I have my own life to live"?

- As far as science is concerned, Tolstoy notes the fact that we

are part of the infinite destroys the recognition of our

significance. His account is in accord with a contemporary

understanding of the levels of phenomena of the world and how

these levels purport to explain the human condition.

The Levels of Phenomena Levels Description Physics This study presupposes reality is explained by investigating the fundamental constituents of the universe: systems composed most likely of fundamental particles, forces, and fields—the terms of which matter, energy, space, and time are conceived. Chemistry Reality is reducible to, and is explained by, the composition, interactions, and processes of atoms. Atoms, composed from sub-atomic particles, combine to form various structures including more complex molecules which compose the various forms and states of matter. Biochemistry Organisms are viewed in terms of the chemical processes of carbon-chains which combine to form the structures and functions of life-processes. It is assumed that biochemistry is no more than complex chemistry. Biology. Studies life-processes in terms of their structure and function are based on the carbon-based macromolecules of biochemistry. Organisms and their properties are based on, and ultimately are reducible to, the same laws of physics and chemistry. People are composed of these complex molecules (an interesting "pile" of molecules in a certain form). Psychology Our minds and behavior are mostly reducible to chemical reactions in the brain. Mental processes or mental states are founded on neural processes which are reducible to, and explainable by, biochemical interactions. Our minds are chemical reactions in the brain Sociology and Political Science The interaction of persons, biological creatures, is based upon the psychology of the individuals and their characteristics and function in groups. In the end, social forces are no more than complex events composed and reducible to those same fundamental particles and forces in physics. - We may as well add that the immense time-periods in recounting

the story of existence from the "big bang" diminishes

the meaning and significance of life as well. Consider the

chart below. My time-on-earth is not really noticeable in the

enlarged scale dating from Homo

erectus.

Age of the Universe Event Time The Big Bang 14 billion years ago Earth's Formation 4.5 billion years ago Homo erectus 2 million years ago Neanderthal Extinction 30,000 BC Farming 10,000 BC Mesopotamia 4,000 BC My Life 1988 AD - The answer of science, then, is that human life is incomprehensible and is part of the incomprehensible and infinite universe.

- Consider, for example, our place in the vastness of the

universe. If it were possible to travel at the speed of

light, then it would take us …

Size of the Universe Speed of Light Distances Measured 11 hours Earth to the "dwarf planet" Pluto 4.2 years Earth to nearest star, Proxima Centauri 100,00 years Earth to other side of Milky Way (our galaxy) 2.5 million years Earth to nearest large galaxy, Andromeda 10 to 12 billion years Earth to the farthest known galaxy

- First, Tolstoy explains that art is an adornment of life,

a decoy of life, a diversion, a way to elude life.

- Why does the working person, the

person with the least theoretical knowledge, have no

doubt about life's meaning? In what ways is Tolstoy's

characterization of this type of person similar to

Russell's characterization of the practical person?

- Tolstoy believes that only irrational knowledge or faith makes it possible to live. He particularly cites the faith of the working people.

- The working people do not fit into the four ways he cites for

dealing with the question of life's meaning:

- First: Ignorance and avoidance of the question.

- Second: Epicureanism—losing oneself in the pleasures of life.

- Third: The "strength and energy" of taking one's own life.

- Fourth: The weakness of just going on and clinging to life.

- Ordinary laborers do not fit into these categories of life's meanings because they do not have the "reasonable" knowledge of educated persons; they have a faith of infinite meaning beyond the illusory finite limitations of the physical world

- Carefully characterize Tolstoy's

conception of faith. In what sense is "faith"

another kind of "truth" for Tolstoy? Is the

notion of "irrational knowledge" meaningful

from a philosophical point of view?

- Faith, alone, can give life meaning. To live humanly is to believe in something beyond proof. Faith is non-rational knowledge.

- Note particularly that, although Tolstoy was a Christian, he is not proselytizing for that religion. He points out that the superstitions of religion are not essential to that faith.

- The faith that Tolstoy characterizes is faith in the

relation of the finite to the infinite. He states that

real faith is that which alone gives meaning and possibility

to life.

- Reflection, arts, and sciences are mere pampering of appetites.

- The meaning given to this life is "truth."

- Note how the definition of "truth" has changed

throughout the essay:

- Truth1 is the attempt to live comfortably.

- Truth2 is the fact of death.

- Truth3 is faith.

- Explain Tolstoy's "arrest of life" from both

a philosophical and a psychological point of view.

- Tolstoy's views on art are summarized in on this site in the æsthetics book Readings in the History of Æsthetics in a chapter entitled, "Art Evokes Feeling".

- Notes are arranged in response to the questions stated below in

reference to "Only

Faith Can Give Truth" selected from Tolstoy's A Confession in

Reading for Philosophical Inquiry.

- Death of Ivan Ilych: The online version of Leo Tolstoy novel, first published in 1886 and translated by Louise and Aylmer Maude, is distributed by the Tolstoy Library. The novel illustrates how an authentic life is made possible through contemplation of death.

- “Irrationalism in the History of Philosophy” Since irrationalism is a dissent from philosophy, there is no irrationalistic tradition in philosophy. Jean Wahl summarizes the thought of philosophers who have rejected the purported misuses of reason in the Dictionary of the History of Ideas maintained by the Electronic Text Center at the University of Virginia Library.

- Leo Tolstoy: An e-text of the biography by G.K. Chesterton, G.H. Perris, et al., first published in London by Hoder and Stroughton in 1903. The site includes many photographs from Tolstoy's life and an assessment of his works. The site is highly recommended as an introduction to Tolstoy's life and thought.

- Leo Tolstoy. The entry by in the 1911 Encyclopedia Britannica reviews Tolstoy's life and thought.

- Leo Tolstoy: Biography, writings, and assessment of Tolstoy with further links from the Wikipedia.

“No matter in what faith a man may have been educated, whether in the Mohammedan, Christian, Buddhist, Jewish, or Confucian, he will in every doctrine of faith find an assertion of indubitable truth, which is recognized by his reason, and side by side with it assertions contrary to reason, which are given out as equally deserving faith. In order to free himself from this deception of faith, a man must not be discouraged because the truths which are recognized by his reason and those which are not recognized by it are given out as equally deserving faith on account of their common origin, and as though inseparably connected, but must understand and remember that every revelation of the truth to men … has always so startled people that it has been clothed in supernatural form …” Leo Tolstoy, The Christian Teaching in The Complete Works of Tolstoy trans. Leo Wiener (London: J. M. Dent & Co, 1904) Vol. 2, 420.

[an error occurred while processing this directive]

This page last updated 12/20/09

© 2006 Licensed under the GFDL